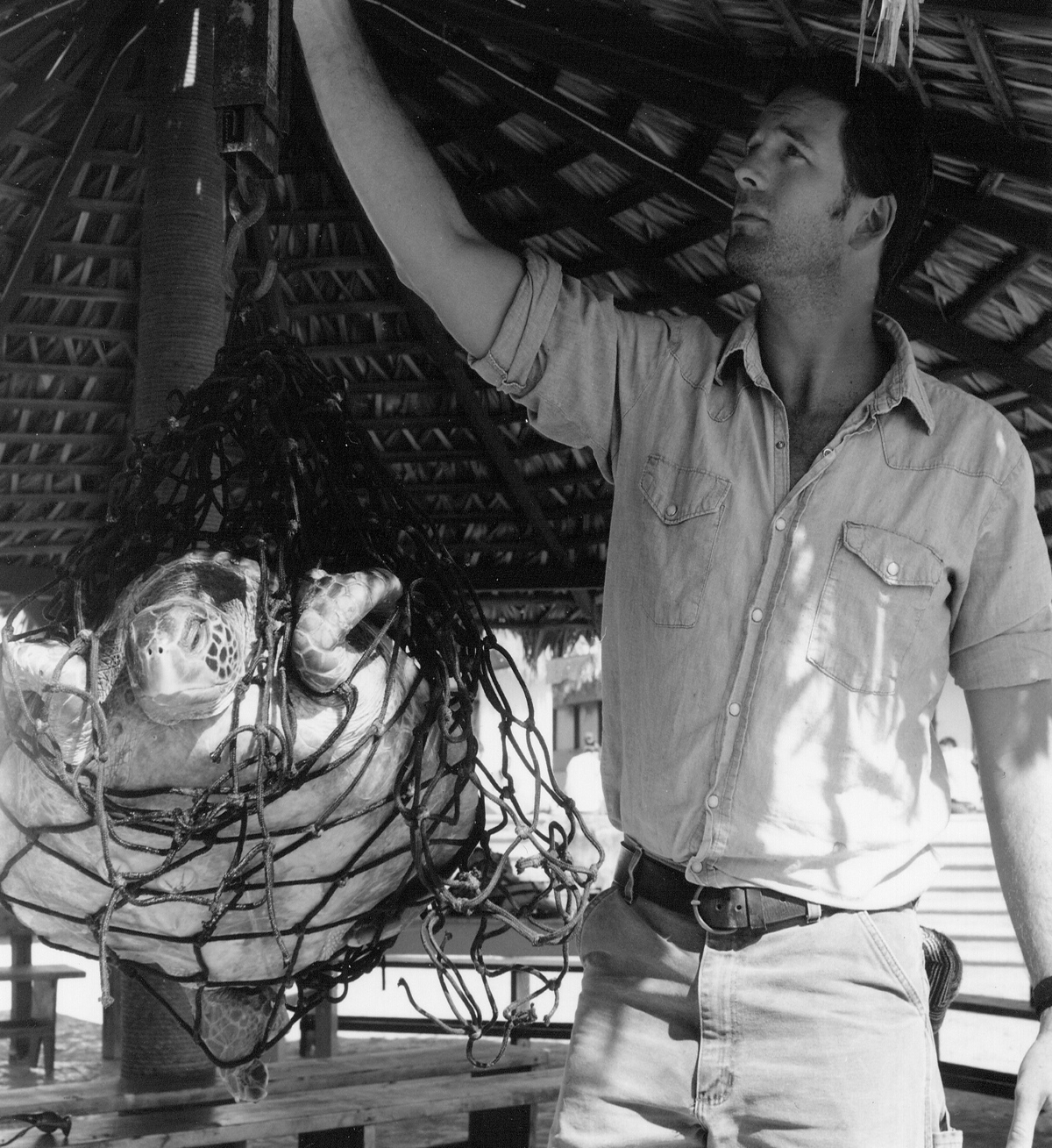

Courtesy of Wallace J Nichols

When it comes to tracking sea turtles, marine biologist Wallace “J” Nichols is first to admit some societies do not care about the reptiles. “Their decline won’t change the lives of most people, but that does not mean we should kill a vital part of an ecological system,” Nichols says.

For two decades Nichols has tracked and studied green, loggerhead, hawksbill, olive ridley, and leatherback turtles along the coasts of California, Mexico, El Salvador, Indonesia, and other parts of the world. He campaigned with indigenous groups in Mexico and held educational seminars across U.S. college campuses. He guided graduate students through field research and reported to U.S. Congress on threats to sea turtles. His efforts, a direct result of the unencumbered extension of his childhood curiosity, were featured in documentaries, on television and radio.

Long track

Nichols developed deep attachment to turtles at a tender age, when he tracked his first leatherback in Chesapeake Bay, ultimately leading him to pursue environmental studies. At a small liberal arts school in Indiana, Nichols took refuge in the university’s nature park. After completing a Masters of Environmental Management at Duke University and a Ph.D. in Wildlife Ecology at the University of Arizona, he began tracking ocean wildlife.

In 1994, he tracked a loggerhead from California to Japan with a transmitter bonded to her shell. For Nichols, Adelita’s 6,000-mile journey west proved successful and served as starting point for marine conservation dialogue. At conferences, Nichols discusses threats to sea turtles. He draws on illegal hunting of turtle for food and eggs. “Because turtles are slow-growing, late maturing animals, as demand surpasses local consumption, the turtles fail to produce, and the population begins to crash,” says Nichols.

Shrimp trawls, gill nets and long lines, plastic pollution, oil spills, boat strikes and disease, a by-catch (accidental catch) further reduce turtle population. Nichols understands the turtles as “flag species” – a symbol for responsible fishing, thoughtful coastal development, clean energy, biodegradable and reusable materials, ocean health, community activism and indigenous rights.

In 1999, Nichols created grupo tortuguero in Baja, Mexico to engage local communities in protecting endangered sea turtles. Through supportive social networks, communities collaborated to safeguard local turtles. In 2000, only two non-governmental organizations and community groups existed; by 2010, there were 36.

grupo tortuguero contributed to the emergence of philanthropic associations. A friend of Nichols, AJ Schneller, is documenting marine conservation issues in isolated communities in Baja, while researching the outcomes of sea turtle murals. “We are trying to show public art spaces can be reclaimed from commercial advertisers and used for the purposes of environmental education and outreach,” Schneller indicates. The group inspired Nichols to raise broader marine conservation awareness beyond Mexico. He founded ocean Revolution to protect the marine wildlife in Mozambique.

His current project, LIvBLUE, addresses whales, turtles, plastic, oil spill, and neuroscience. The collaborative initiative engages businesses, universities, Ngos, and individuals to act on the protection of the Earth.

Fostering change

In Baja, Julios belongs to the Bahia Magdalena indigenous group. He had spent all his life hunting loggerheads for a living. He met Nichols in 1999 when he was working as poacher. Julios blamed culture and ignorance on poaching. “i never met someone so concerned with the protection of our natural resources,” comments Julios about Nichols.

Julios inhabits an area where eating turtles remain a fabric of life. Survival of local and isolated communities is dependent on turtle meat, which costs $2/kilo. However, anyone aged 20 and younger knows that eating turtles is illegal, says Scheller. Fines are high and poaching is punished by jail. The risks are higher for turtles than lobster and shrimp. “It costs $5000 a week poaching shrimp,” remarks Scheller, “and you could make this in a week poaching turtles.”

Former poachers like Julios and some local fishermen now work to help grupo tortuguero. in a decade, turtles sold on black market reduced significantly. local regulations have tightened; lawsuits persuaded the municipal government to curtail activity in the region.

At nearby Seri (Comca’ac) indigenous group, Nichols organized many campaigns aimed at long- term conservation. There, the turtle conservationists are the only ones in the country with hunting permits. In two decades of collaboration in Mexico, tens of thousands of large turtles were saved and hundreds of thousands of hatchlings released.

Solid barriers

Despite the mounting support, Nichols admits to barriers. “Bureaucracy, inadequate funding, corrupt officials, our addiction to fossil fuels and plastics, remain a problem.” In Asian countries, sea turtle consumption is permitted and encouraged with little support in conservation and legislation. In the Middle East, the lack of enforcement on the part of governmental agencies and corruption in state agencies has slowed the conservation process.

Global climate change, loss of nesting habitat and beaches, and rise in sea level, are a constant threat to the turtles. The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) has reported the global decline of loggerheads. “However, there has been tremendous attention around the world and people are beginning to see it,” says Nichols. At previous conferences, he met with journalists and academics inspired by his research. “Some people see me as incredibly narrowly focused, and some as a generalist,” he says. “But without adjusting culture and crime, politics and corruption, little can be achieved for the sea turtles.”