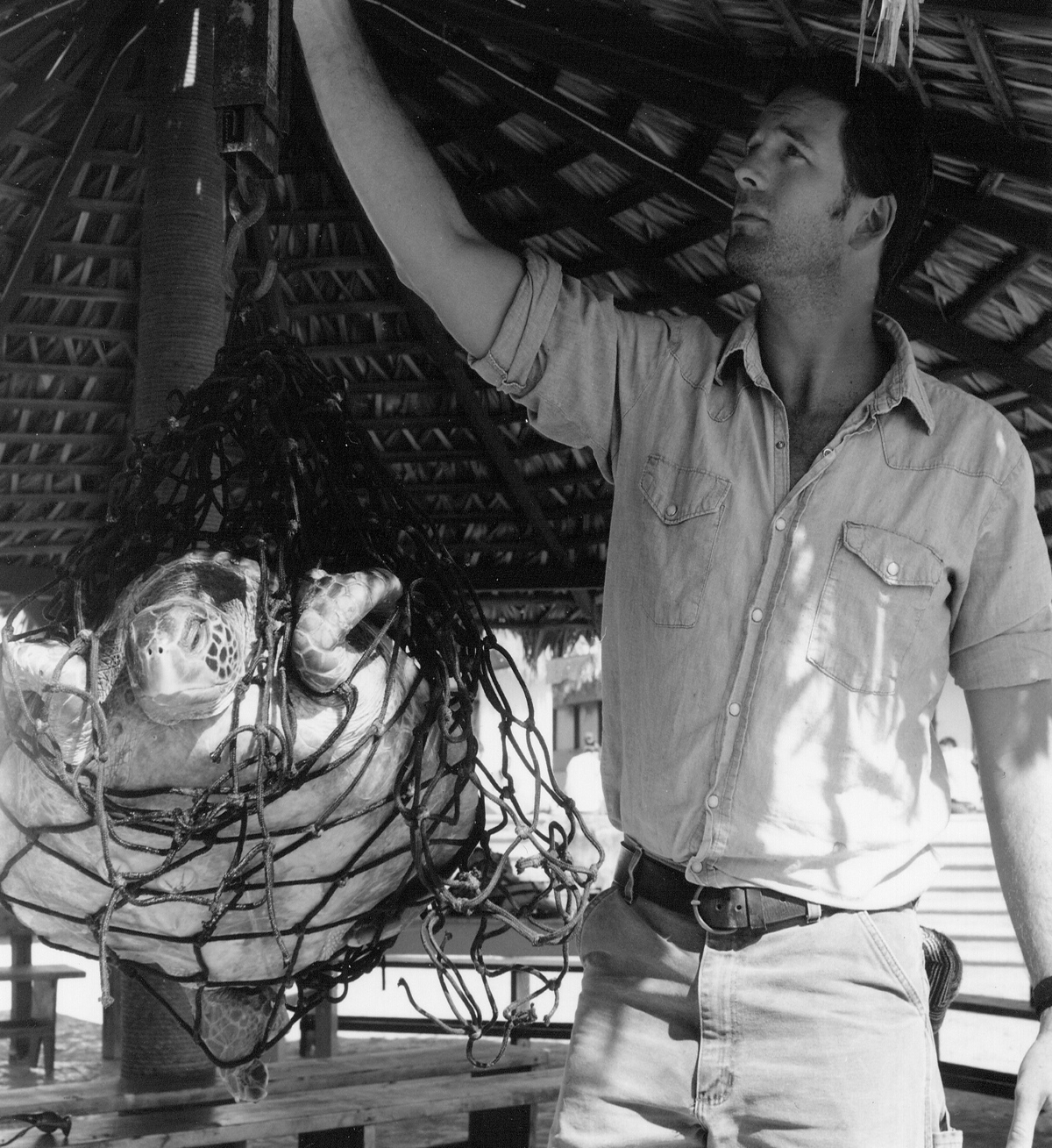

One a blistering day in 1942, Harvard Professor Richard Evans Schultes cuts through the thick vegetation in the northwest Amazon of Colombia. He is a resident of the jungle, combing its remote reaches for his research; seeking out new species of plants endowed with powerful healing agents. The father of ethnobotany often lived among some two dozen indigenous tribes, and collected over 20,000 botanical specimens during his lifetime, most notable being the hallucinogenic plants used by tribal healers and shamans.

Twenty years later, a one-time student and protégé of Dr. Schultes, Harvard Professor Tim Plowman, embarked on a similar exploration. Recalling Schultes’ research in hallucinogens, Plowman insisted the shamans show him the sacred plants, and prepare him a tasting of what they called a “dangerous message of the forest.”

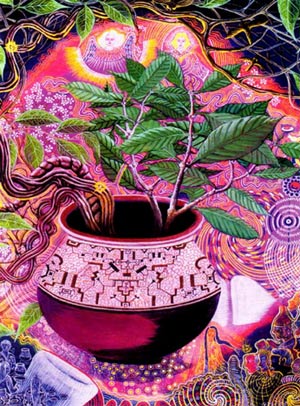

The old shaman cut a piece of bark, which grew in thick, double helixshaped coils around rainforest trees, and contained psychoactive and sedative drugs called beta-carbolines, and brewed it with DMT—a natural psychedelic from another species of plant. Moments after swallowing the bitter, brown, thick stew known as “Ayahuasca,” the young professor experienced vertigo—his head spun, stomach ached, and his body ran with chills. The shamanistic ritual caused Plowman to suffer a reaction with maddening intensity, but fortunately the effect lasted only ten minutes. Frightened, he fled the shaman, wandering for hours through the jungle until finding shelter in an abandoned town jail.

His experience led him to explore Ayahuasca within the more controlled environment of Harvard University. He became famous amongst his colleagues and students, as well as anthropologists and ethnobotanists across the United States for his research. It was the 1960s, and even though much of America was exploring psychedelic drugs, there were strict bans on its usage, and little funding was provided for the research towards its positive contributions to health.

Anthropologist, Zen Buddhist and lysergide (LSD) researcher, Joan Halifax arrived to Harvard a decade later to shed light on the positive aspects of psychedelic research. Her lecture was well received, and focused on end-of-life fear reduction in terminal patients who used psychedelics to ease distress.

Meanwhile, Alex Grey, who dissected cadavers at Harvard Medical School’s Anatomy Department, recalled “general skepticism and paranoia from faculty” as the Zen Buddhist gave her famous speech. Grey would often trip on LSD and Ayahuasca (he calls it the “Green Jesus” or second in which individuals realize the divinity of nature). While at the Mind/Body Medicine Department, explored healing energies using scientific experiments to inspire his medical illustrative body of work called “The Sacred Mirrors.” The series of life-size paintings explore the body, mind and spirit, presenting the “physical and subtle anatomy of an individual in the context of cosmic, biological and technological evolution,” as he writes on his personal website. Through his work he hopes to connect individuals

with their inner psyche.

Grey’s friend Daniel Pinchbeck is a new age philosopher and advocate for psychedelics. Born in 1966, the year the U.S government banned LSD, Pinchbeck meandered with other Bohemian hedonists in the NYC neighborhood of the Lower East Side. His mother, Joyce Johnson was a famous “Beat” poet—a term used to describe a group of post-WWII writers who often experimented with drugs and sexuality, rejected materialism, and embraced Eastern religious traditions such as Buddhism and Taoism. Pinchbeck’s early introduction to an alternative lifestyle blossomed at Wesleyan College where he tried LSD and psilocybin “magic” mushrooms. He studied ecology and philosophy but soon became preoccupied with the ideals of nihilism, and eventually dropped out to pursue a writing career.

The New York Times Magazine chose him as one of “Thirty Under Thirty” destined to change our culture through his literary work at Open City, a journal Pinchbeck founded featuring prized authors like Richard Yates and David Foster Wallace—now dead. Pinchbeck wrote for The Village Voice and Rolling Stone, but was “blacklisted” by Esquire and The New York Times for his radical views. After years of becoming intellectually dissatisfied with the media’s conventional mindset, the 29-year-old tried to find stimulation elsewhere. He found himself in a Manhattan apartment with strangers and took a swig of a jungle potion. Wearing a blindfold and adult Depends diapers, the Ayahuasca caused him to envision pigs chewing corpses lying in a slum gutter and then… moving images of bright green vines in front a blue waterfall. As in Plowman’s case, the high only lasted a few minutes, and ended with uncontrollable vomiting

Thereafter, he traveled across South America, visiting Andean, Aztec, and Amazonian indigenous tribes to learn about the healing properties and governing spirits of hallucinogens. In Brazil, where Ayahuasca is legally recognized as a medical and cultural patrimony, Pinchbeck attended religious ceremonies of Santo Daime. He compared his internal experience with the potion to that of mushrooms; a beautiful place that “feels like having a mental envelope around the earth,” he recalls.

Pinchbeck greets me in a neighborhood café and shares stories of Burning Man and the sacred earth. Burning Man, the famous art, sculpture and music venue in California, draws many subcultures: punks, ravers, goths, pagans, and hippies. They often take psychedelic drugs to explore realms in which their consciousness travels beyond boundaries, painted with abnormal patterns, brightened colors, and enhanced natural elements. “Some realms are mythical, in which case Ayahuasca guides individuals,” he tells me. So each year he guides a retreat to Latin America in order to explore this world of botany, cultural history, mysticism, and alternative medicine.

Countless numbers of articles, three books, and one website later, Pinchbeck has decided that psychedelic drugs are less threatening than manufactured prescriptions. According to his research, 27 million of Americans alter their state of mind and mood, chemically, with antidepressants such as Zoloft and Prozac. These drugs, rather than being demonized, are sold for profit by pharmaceutical companies and promoted by medical professionals.

In contrast, Ayahuasca is a natural remedy that helps treat depression, trauma, alcoholism and anxiety disorders. A controlled study at UCLA’s School of Medicine found that church members of Brazil’s Iniao de Vegetal (UDV) experienced remissions without recurrence of their addictions and disorders. Additionally, blood samples showed the unexpected: Ayahuasca increased the number of serotonin receptors on nerve cells.

Already American agencies and universities are making decisions based on data rather than politics. What used to be hailed as a new tool of psychiatry, then as illegal substances, is now being evaluated as miracle medicine. Multidisciplinary Approach to Psychedelic Studies (MAPS) is sponsoring research using mushrooms to treat illness while anthropologist Bia Labarte is pushing the therapeutic benefits of psychedelics into the mainstream. Surprisingly, Pinchbeck tells me that there are case studies of people’s spontaneous remissions from cancer.

A short walk from the café, Pinchbeck escorts me up a flight of stairs to his apartment. His father’s large colorful abstract painting takes up one wall; and opposite, the writer’s modest library shelved with books on spirituality, art, and hallucinogens. He sinks into a couch and flips through Grey’s illustrations, weaved with themes of death and transcendence, human psyche and the cosmos. He looks tired, and confesses to losing sleep due to writing his latest book on improving society, ruined by environmental and financial crisis.

He shows me a silver tray filled with memorabilia from festivals and conferences; dried sage and quartz pendants, hardened mushroom caps and wooden handmade bongs. He places a sacred Shamanistic branch and a black obsidian shard into my palms, before taking hold of an orgone accumulator used to ward off bad weather. But clasps of thunder are already rolling in our direction. I would imagine that like the visionaries of hallucinogens before him, Pinchbeck uses these items for the positive benefits of psychedelics, advocating “the sacred medicine slithering out of the jungle, finding human vessels for people to explore,” he says jokingly.

Ayahuasca like many other psychedelics destroys space and time, but bridges the paradoxical subconscious and conscious worlds. Pinchbeck is preparing for next’s years global awareness campaign, Unify Earth, in hopes of reconnecting millions of people to their soul through prayer, meditation and psychedelics. The event will be held at different locations, scheduled days before tribal cultures foretold the end of one age and the beginning of another. Rather than foreseeing doom and destruction as the Mayans had, he anticipates a new era of cosmic renewal bearing advancements in astrophysics, calling on indigenous prophesy to heal the mind and spirit.

Additional reporting by Eric Joseph Reitmeyer

The full featured article in RagMag November 2011 (PDF)

[issuu width=550 height=359 pageNumber=29 backgroundColor=%23222222 documentId=111208064108-d6b86c763aac4be887b750c28b54b187 name=ragmag_nov_2011 username=ragmag tag=3d unit=px id=34f4ddee-f9a7-5d43-3062-057a1701e2b1 v=2]