There are only a few days remaining before American legendary musician Leland “Bruce” Sklar turns 64, and the songwriter and notable bass guitarist is pacing circles inside his Los Angeles home. The passing of another year is not a special concern to “Lee”, instead he is roused by his twelve-hour studio session of cutting more than a dozen tracks for a local musician. One might expect this workload to warrant a say f rest and relaxation. “Oh no,” he says, “I’m not good with one of those.

Gifted with a type-A personality and penchant for control, Lee has spent four decades hard at work in the studio and touring with pop, rock, folk, and artists from Ray Charles, Phil Collins and The Doors, to Diana Ross, Rod Stewart and James Tylor. Not limited to plucking his bass, over the years he has contributed lyrics to nearly 25,000 songs, and co-produced over 2,000 albums. Adding to his impressive catalogue are contributions to several film and television soundtracks, such as Legally Blonde and Coyote Ugly.

He credits his popularity to immense luck and a simple methodology: “Don’t deliberate over jobs, show up, and get it done.” It works. He’s always booked. But Lee has never gotten around to writing his own songs. He admits that laziness is partly to blame, and that much of his studio time is dedicated to someone else’s material. Lee’s journey began at the age of five, when his musically inclined parents traded their Wisconsin hometown of Milwaukee for the Californian party city of Los Angeles. There he developed his skills, and became a self-described “classical snob”, winning several achievement awards for his piano recitals by the time he entered junior high school. “I used to play along with my parents’ Hi-Fi” he says, “Everything from the Beatles to the Righteous Brothers to James Brown and on and on.” This diverse interest in music was the impetus for becoming a studio musician, which allowed him to participate in several genres.

Music served as a backdrop for a momentous occasion in 1957. Lee was in attendance at Hollywood Bowl’s Gershwin Nights when the orchestra suddenly gave pause, and everyone watched as Sputnik sailed overhead. “A shiny dot in the sky” he remembers, “An amazing thing since no-one had ever seen a man-made object in space.” His introduction to the bass came during his high school years, when his music teacher handed him the guitar during class. He soon fell in love with the instrument, and began performing at weekend garage band sessions and school dances. Lee’s career path was never decidedly toward music. He once entertained the idea of becoming an oceanographer, until the day he met James Vernon Taylor. The two musicians established a deep friendship, moulding a musical relationship based on lyrical attachment; singing songs about birth, death, marriage and divorce. “Taylor was a hot commodity at the time recalls Lee. The fifth-year college dropout was asked to collaborate on Taylor’s world tour, which ultimately turned into a two-decade long musical episode.

It was on tour with Phil Collins in late 2005 that Lee landed in the Middle East for the first time, playing shows in Dubai, Tel Aviv, Jerusalem, and finally, Beirut. Luckily they had arrived two months ahead of the violence that swallowed the city in 2006. “It so sucks to see the shells on the news,” Lee recalls. The show was a success, but they nearly missed their performance, as the crew were forced to endure some logistical setbacks. The equipment was held up in Tel Aviv awaiting clearance, so they circumvented the checkpoint by renting a Russian airliner to fly their instruments to Cyprus before landing at Hariri International Airport. Lee comments on the discord with a fluster, “When you play music for anyone in the world, everyone is the same person and they enjoy it. But when politicians get involved it all goes to crap…this religious-political bullshit.”

The word “bullshit” might enter the conversation when discussing the current music scene, since technology has redefined the way music is made. Commenting on the digital era of Pro Tools – a software computer program that adjusts pitch via auto tuning – Lee says, “With digital tech having been introduced, musicians don’t need $1 million worth of high-tech studio equipment. Instead they spend $300 to make it sound credible.” Nostalgic for the garageband, Lee laments his generation’s home-grown jam groups. “Juices that makes the music great is shared when musicians are working together,” he says enthusiastically. Unfortunately the trend has band-mates remotely recording pieces of music and emailing them to each other. Lee prefers to travel and record in person, though he rarely packs the amp anymore, instead plugging into the computer. Yet Lee credits the industry as “ninety six percent incredible, 4 percent sucks,” most likely placing Lady Gaga in the four percent. “Gaga is a talented girl—a rehashed Madonna who is great in theatre but not in music,” Lee comments, emphasizing that most popular music produced today is dependent on the studio engineers playing with their toolboxes.

Lee’s life these days is somewhat of a balancing act. Though he still fields calls from musicians and producers, there are rewards outside the sphere of music that keep him fulfilled. “My life is only sixty percent music,” he notes. When not playing he can be found gardening, tuning his 1923 Ford Model T “Hot Rod,” and caring for his two Basset hounds. This equilibrium, along with his established work ethic, has shielded Lee from the stereotype of a star soaked in sex, drugs and Rock & Roll. He is happily married for forty-one years to a “very independent woman”, and has always steered clear of drugs and alcohol. “Drinking never appealed to my pallet,” he admits, “witnessing friends on bad acid trips, shooting meth and dying of overdose is nothing sexy…it sucks.” It is intuition that guides him through an irksome environment of high profile, atrophied artists often lacking in direction. The ability to focus without choking “when the red lights come on,” he remarks, is paramount. Many bands have failed due to tripping on psychedelic drugs rather than finishing their albums in the studio.

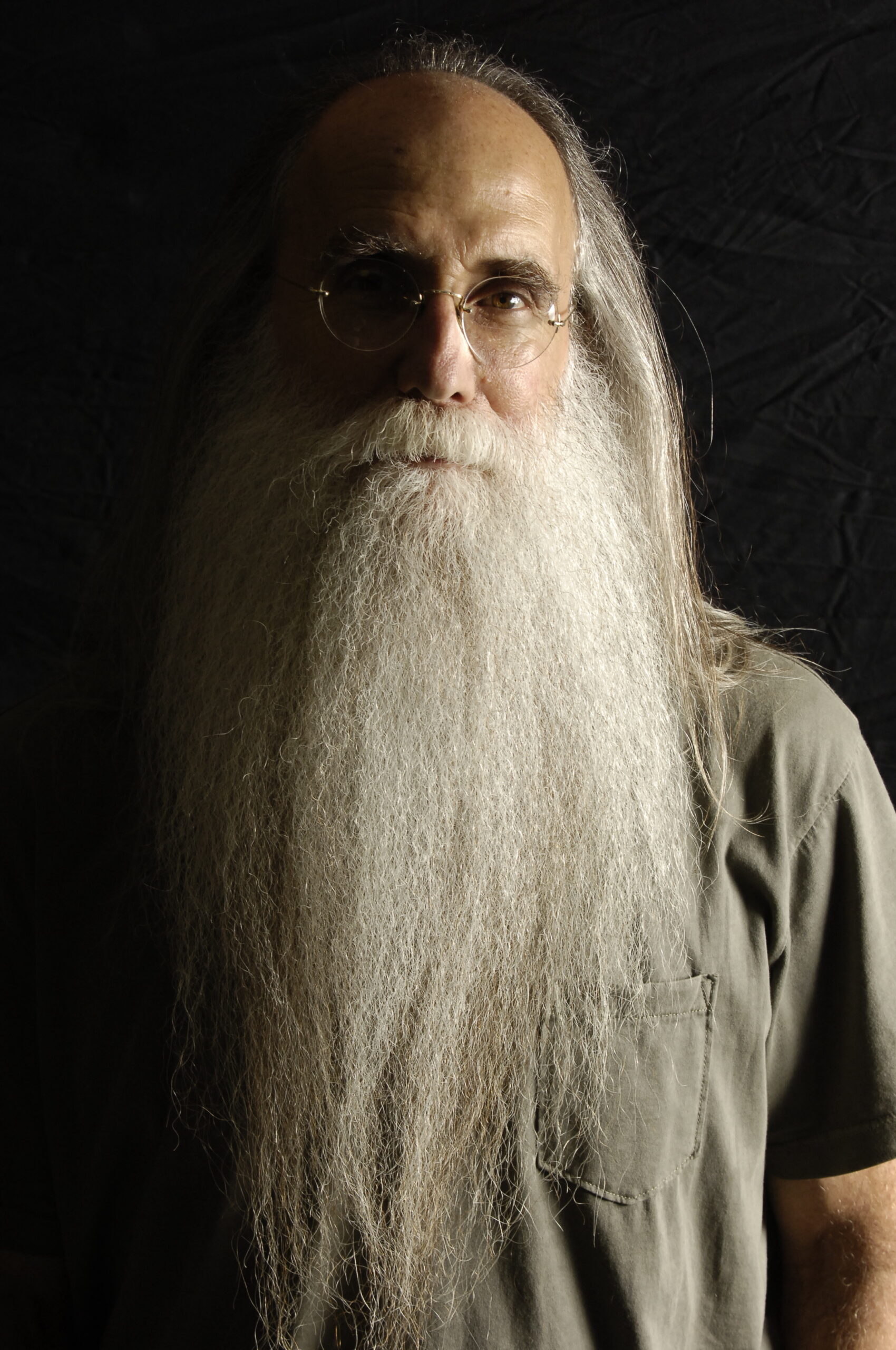

Today, Lee’s frequent visits to the round-table discussions at the Downtown Los Angeles Grammy Museum gives young musicians an opportunity to hear about the original days of rock. He complies, and offers a few tales to his listeners. To him, the era was “amazing”: being in Berlin before The Wall fell, in Russia before Glasnost, or in Japan at twenty degrees below zero during the snow festival. For me, he recounted an experience from a layover in a Glasgow airport, where due to his trademark beard, a young boy took Lee for Santa, and superstar icon Phil Collins was mistaken for his little elf.

For a musician with such an eclectic history and list of friends, one might think an autobiography would be an appropriate enterprise. Yet Lee has no interest, admitting he has never kept a journal. Instead he refers to his memory, where he has stored a virtual logbook of experiences. “It’s up to the people to check my history” he says, “and not for me to sit here like an old fart talking about the good old days.”

Though waxing poetic may not be a favorite pastime for Lee, upon reflection the sharp-minded old hippie is immensely thankful for the long ride.

Additional reporting by Eric Joseph Reitmeyer

The full featured article in RagMag July 2011 (PDF)

[issuu width=550 height=359 pageNumber=34 backgroundColor=%23222222 documentId=110807082500-ecae37cdf18840dbb76152e4c6f4897e name=ragmag_july_2011 username=ragmag tag=beach unit=px id=d68e830b-04ed-4070-53d7-4f768f9444f1 v=2]