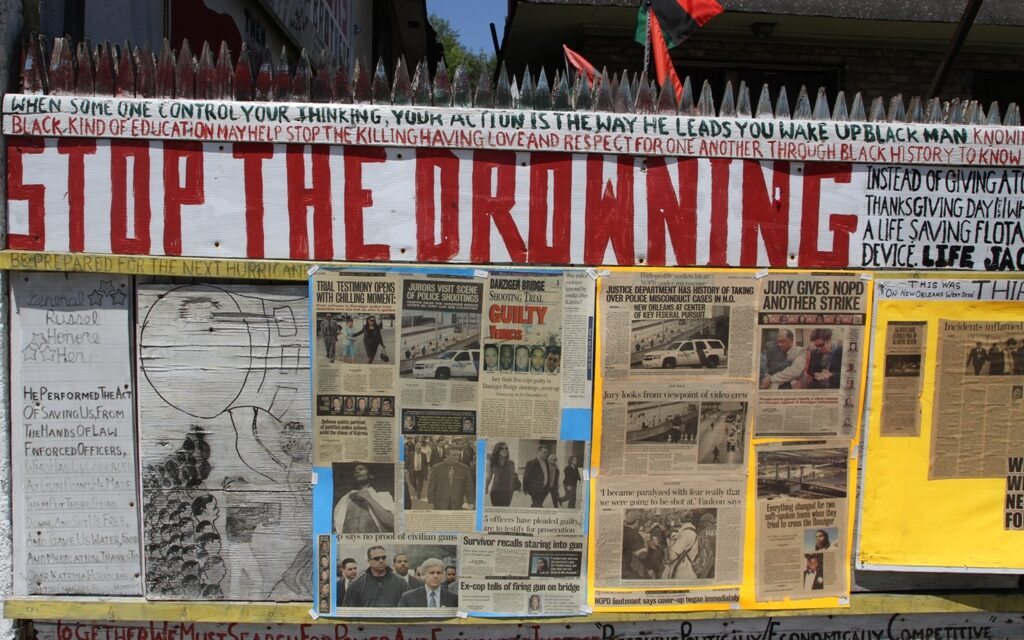

Protest posters on walls for 6th Anniversary of Hurrican Katrina

On the sixth anniversary of the perfect storm that drowned more than two-thirds of New Orleans, and obliged over a million of its residents to evacuate overnight, gray clouds of smoke veil city blocks. A year ago, nearby marshlands dressed in coats of oil—thanks, BP!—coughed up billowing smoke as a result of a stubborn fire that burned for more than three days. Recently, a tropical storm washed ashore from the Gulf of Mexico.

Katrina surges into the Big Easy

Storm surges from hurricanes are an integral part of life in Louisiana’s famed port city, nicknamed “The Big Easy.” The lower Mississippi River meanders in loops over its flooded plain. Each spring, as the snow melts along its northern tributaries, high water descends. These cycles have repeated themselves for over thousands of years, leaving annual silt deposits along the banks that have gradually built up to several feet. Consequently, the highest ground in southern Louisiana is along the river banks. Falling rain drains away from rivers and bayous into swamps at the rear of the river banks. The Mississippi levees held, until category-3 winds and tidal surges pushed a barge into the embankment, flooding scores of Delta communities— including our big lady, New Orleans. With eighty percent of the city drowned in up to fourteen feet of water, The United States Army Corp of Engineers responsible for levy upkeep turned a blind eye, while the Federal Emergency Management Agency dispatched close to a thousand mobile trailers that sprayed chemicals to keep rodents and other pests out.

Non-profit organizations step up to the plate

Brad Pitt finances solar panels in the Lower Ninth Ward, severly flooded by Katrina

Mobile homes are sitting in a deserted yard in the eastern part of the city, being studied by a high school football coach. Mounting solar panels on their roofs, he hopes to produce enough energy to sell to the city grid. Brad Pitt had the same idea. His non-profit organization, Make It Right, has installed solar panels on Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED)-certified, newly built two-story homes in the Lower Ninth Ward—a neighborhood that was completely flattened by water, with its four thousand homes coated in mud. Pitt and his team are seventy-five houses short of reaching his goal of one hundred fifty houses. Hike for Katrina has planted trees. Habitat for Humanity has donated jeans material to insulate houses. Another non-profit organization has donated tents. Tulane University architecture students and faculty have designed blueprints for new housing.

The city government introduces initiatives

The city is promoting solar technology by introducing citywide initiatives. “Its Energy Smart Program provides short-term and long-term rewards for those who make energy saving investments in their homes and businesses,» says Cathy Herren, director of Housing Initiatives for Entergy New Orleans. By partnering with the United States Department of Energy for the adoption of a tax credit that benefits the solar industry, the city falls short of the finish line.

Help from the federal government

The federal government might have a chance of succeeding, by supporting green-conscious non-profit organizations that are looking to solve problems. The Environmental Protection Agency has already invested over $30 million in grant money for the following recipients: The Louisiana Green Corporation, which installs cellulose and fiberglass insulation, selling salvaged cypress wood (native to Louisiana) materials that otherwise would have ended up in a landfill; Global Green USA, which designs sustainability plans, urban green design proposals, and climate action plans for homes, and installs solar panels on schools; and the Louisiana Bucket Brigade, which encourages citizens to take their own air samples, a step that is needed to study the damaging effects of the Horizon Deepwater Oil Spill.

The greening of Louisiana is a long way off

New house foundation left abandoned in the Lower Ninth Ward. Grass can grow up to 10 ft on private and public property - maintenance according to city budget that often reaches the Ward last

In spite of all these efforts, the race for green technology has fallen short. Four megawatts of energy installed across the state has not been enough for significant progress. Legislation has been limited; only recently several bills have begun to snake their way through the state legislature. With sluggish progress on the renewable energy portfolio standard, clean energy advocates remain skeptical. Not to mention the poor reconstruction of levies, which hold little promise of safety for New Orleaners.

Such failures are related to oil and gas industries that dictate how money is to be spent, as well as the federal government’s improper redistribution of profits from royalties. Louisiana is a poor state with a multitude of industries that are capable of cleaning up its mess only if the federal authorities play a fair game. However, until the state cleans up its act, the green bar will remain low.