Yellow mini buses zoom along highways bending around residential slabs of concrete. They are haunting

relics of the Soviet regime, the fabric of their totalitarianism still woven into the Ukrainian landscape.

The monstrous Brezhnev-era leftovers disappear in downtown Kiev, but are replaced by the grim hospitality of the former Soviet Union. Fortunately, young women add colorful flavors to such appearances, with their full lips painted red, their brand name boots shaded silver, and posh fur coat lining dyed purple. During WWII the main boulevard of Khreshchatyk housed booby traps for German soldiers. Today the pedestrian zone has become an unlikely runway for expensive tastes rivaling those of NYC’s Fifth Avenue and Paris’s Boulevard du Crime.

Gold-capped churches add to the palette of downtown. The eastern Orthodox denomination is responsible for erecting thousands of these round oniony structures across the country. In Kiev, gilded turrets, spires and domes—some almost 1,000 years old—laminate the city, setting the stage for a beautiful fairy-tale. Foundations for new churches rise at the feet of many apartment complexes, which on average house up to five hundred devout residents.

More lavish examples can be found throughout the historic sections of Kiev. The Kievo-Pecherska Lavra, a cluster of churches nestled on the grassy hills above the Dnieper River, contain world-famous catacombs and channels of underground medieval caves, some of which supposedly stretch as far as Moscow. Entering the caves by the Church of the Raising of the Cross, many descend into a labyrinth of candlelit corridors that serve as tombs for hundreds of mummified monks, more than nine hundred years-old.

Sophia’s Cathedral, a symbol of the Orthodox world order and simultaneously a Byzantine architectural wonder, is the city’s oldest standing church. During the Rus Empire, the predecessor of modern Ukraine, and not, as locals emphatically point out, of Russia, the cathedral became an intellectual center for its educators and literates. The kingdom of Rus preserved its many mosaics and frescoes, originally dating back to the 11th century, until the Mongols sacked the city in 1240 destroying the ancient city’s main entrance, Zoloti Vorota, modeled after Constantinople’s Golden Gate. Similar to the Hagia Sofia in Istanbul, the Cathedral’s decor has maintained its original design. Significantly, Kiev is the birthplace for eastern Slavic civilization which covers the Ukraine, Belarus and Russia.

In the past decade Kiev has been hit with western waves of modernity. In 2004, the Orange Revolution marked a rift with the previous era as Ukrainians made their pro-democratic demands on the central Independence Square. The new government was extremely ineffective and disappointing, but less corrupt, and now the man who perpetrated the Orange Revolution fraud, is president. The western-leaning order formed new markets and free trade agreements. The real estate industry began incorporating lighter materials like brick and glass into their blocky construction projects. Hyatt and Radisson hotels adopted these materials, but older ones were left with hideous concrete renovations.

Recently Ukraine caught the European Union’s attention after winning the joint bid with Poland for the 2012 European Soccer Championship. Furthermore, the EU is giving Ukraine a thumps down for the trial and imprisonment of its former prime minister for her secret oil and gas deals with Russia. The event has stalled a free trade agreement ratification, and EU integration. During my October visit, stampedes of protestors awaited patiently for the verdict as the SWAT-like teams of policemen locked arms along Vul Khreshchatyk. Yulia Tymoshenko supporters and opponents erected a “makeshift tent city,” enjoying free political expression along the boulevard.

Despite recent reform, remnants of the Soviet past continue to survive. Old vendors, most likely former soldiers, adorn the Andriyivsky Uzviz. The historic descent connects the city’s Upper Town neighborhood to the medieval and merchant Podil neighborhood. Along the uneven cobbled walkway, below the blue St. Michael’s Gold-Domed Monastery, they sell goggles and helmets, medals and uniforms borrowed or stolen from the former regime. A few of them resort to cosmonaut Yuri Gargarin shirts and Osama bin Laden stacking dolls called matryoshky.

Public monuments serve additional reminders of the hammer and sickle insignia. Former President Viktor Yushchenko nearly exhausted public funds to build the Holodomor Memorial, dedicated to close to seven million victims of an artificially induced famine created by dictator Joseph Stalin. Meanwhile, the titanium statue of Mother Homeland, with her raised Sword and State Emblem, hovers over a distinctive memorial of carved WWII heroes. The soldier’s and workmen’s chilling expressions bring back childhood imagery of Soviet-occupied Czechoslovakia.

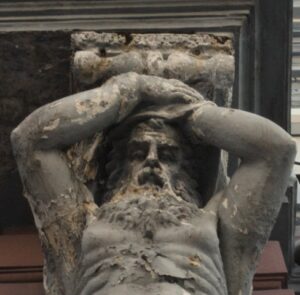

Many political descendants kept the statues, secured new governmental posts, and privatized industries. They held receptions inside the Chimera House, adorned with terrifying sea creatures carved out of cement—a tribute to the owner’s daughter who lost her life to seaside waves. Similar to the gargoyles leaping from the baroque churches of Prague, the stone creatures cast a frightening glare. In those days, old comrades feasted on scarce black caviar and built villas along the riverbank. Like the oligarchs they bought tons of fur and parked their cars inside pedestrian-friendly squares. Meanwhile residents were forced to listen to the noisy refrigerators and paid high rent for crumbling concrete.

Compared to most transitory systems of government that spoil the fun for its citizens, foreigners like me find the various changes entertaining. Inside high-speed Kievan metro stations, old women known to Eastern Europeans as babushkas still wear their head scarves, and warm their palms with sleeping kittens. Another flashback to old Czechoslovakia: markets dressed with woolen vests and slippers imported from Mongolia and Belarus, gardens adorned with beehives and black currant handpicked by babushkas, and forests overgrown with mushrooms.

In contrast, mushrooms found in chestnut forests near Chernobyl grow the size of footballs. Located just two hours from Kiev, the city operated Soviet’s notorious nuclear power plant. But twenty-five years ago, radioactive waste from reactor no. 4 spilled into nearby waterways that headed downstream towards the capital. Clouds carrying dust particles spread across Europe causing many children to develop radiation related diseases. First response firefighters perished within hours, civil workers within months and formers residents within a first few years. Looters sold scrap metal, furniture and jewelry for Kiev markets, poisoning many as a result of the radiation. A concrete and metal sarcophagus exists over the no.4 reactor, and the EU is currently raising funds for a new cover.

On the bus ride back from Chernobyl, I couldn’t stop thinking of Stalin’s grotesquely magnificent power, of foul reputations haunting the country, of the women and Orthodox gold that lift the city from its dull Soviet mold. The country deserves a chance, at least from some Slavs who shyly reference Kiev to a precious gem stone, and from tourists whom no longer feel frightened by its pragmatic way of life.

The full featured article in RagMag December 2011 (PDF)

[issuu width=550 height=359 pageNumber=135 backgroundColor=%23222222 documentId=120109105339-ed6e98bde01746e7ace1d1e4f26dcb57 name=ragmag_december_2011 username=ragmag tag=chelsea%20davine unit=px id=8364cccf-b6e4-0170-a713-a64ab37b08c5 v=2]