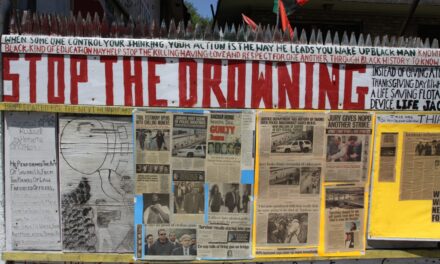

John speaking at an all day anti-drug event at the Church of Scientology in NYC. Courtesy of the Church of Scientology.

Slipping through the revolving doors into NYC’s Church of Scientology is like walking into a space-aged Barnes & Noble. Colourful theology books and self improvement DVDs line the shelves and countertops within the atrium, while its high walls are used as a message board delivering an inspirational quote from L. Ron Hubbard. My first impression of the slick marketing was interrupted by a receptionist, who beckoned me to the front desk with an enthusiastic smile.

The Church employs a young staff, and they are sharply dressed in black uniforms, sporting gold pocket squares and Scientology cross pins. They move about the environment with polished appeal, though their self- assuredness at times appears fabricated and mechanical. The president of the Church is Rev. John Carmichael, who although was initially reticent, welcomed me into his lair and acted the pleasant and congenial host.

We walked the steps to the mezzanine, which resembles a science fiction entertainment center. Walls are paneled with digital screens and touch pads where interested parties shuffle through a brief history of Scientology founder L. Ron Hubbard, as well as an introduction to the tenets of their philosophy.

As stated on the Church’s personal website, the principles of Scientology are: “You are an immortal spiritual being; your experience extends well beyond a single lifetime; and your capabilities are unlimited, even if not presently realized. Furthermore, man is basically good. He is seeking to survive. And his survival depends upon himself and his fellows and his attainment of brotherhood with the universe.”

Courtesy of the Church of Scientology

A true Renaissance man from Nebraska, Hubbard wrote the self- help treatise Dianetics in 1950, from which Scientology was born. The New York Times bestseller explores a metaphysical relationship between the mind and body. It tries to answer the following testaments: Did one do as one intended? And were people glad one lived? In his first, Hubbard recorded three thousand tapes and over twelve thousand manuscripts on man’s personal quest of understanding himself.

Scientology claims to increase the spiritual abilities of individuals through the rehabilitation of the mind and body. Through training courses, seminars, and evaluation tests, wayward individuals turn personal grief into happiness by focusing on the human spirit. All for a $400 annual fee. This generally attracts four groups of people: high-profiled opinion leaders, assertive and confident individuals, ill-fated law-breakers, and reconciled drug-users. The Churches of Scientology are separate corporations, with their own Boards of Directors and local executives who make decisions for their churches.

Since Scientology’s inception in 1954, there are now close to ten thousand Churches, missions and affiliated groups in 165 countries. Last year, six new sites opened, including Brussels, New Mexico and Washington D.C., as well as in urban city centers across California. In February, the Church opened its branch in Moscow and filled it with a staff of over 200. Meanwhile John Travolta opened a branch in Florida to commemorate Hubbard’s 100th birthday anniversary. A Church-issued report to Carmichael stated that with assets and property value doubled since 2004, with over seventy newly acquired buildings around the world, and with 125,000 new members (20 times the previous levels), the Church is showing no signs of slowing down.

The key to the Church’s successful expansion are its packaged social outreach programs, which advocate positive principles like staying away from drugs and living a moral and decent life. At Operation Drug-Free Earth, one of the largest non- governmental anti-drug prevention programs, the Church claims that drug-rates drop when students are provided with the facts on damaging effects of drugs. The program also delivers on-site seminars to two thousand prisons worldwide including South Africa, where prisoners arguably show improvements to complying with probation— restitution, fine payment and community service—after completing the program.

Partially funded by the government, their The Way to Happiness program, a “common sense guide for better living,” primarily targets prisoners in rehabilitation and individuals critical of a society steeped in moral crisis. Close to seven thousand dollars will fetch six thousand booklets of your own customized edition of The Way to Happiness. Carmichael and I embarked on a tour of the premises. The seven floors are meticulously maintained, with elaborate lighting and signage strategically placed, though somehow the space exudes an artificial exterior despite their penchant for theatricality.

The religious institution can easily be mistaken for a wellness center or spiritual university. On the 7th floor is the Purification Center, a rehabilitation center where individuals sweat for up to five hours in a sauna and are then inundated with B3 Vitamins. The idea is to flush toxins, chemicals, and drugs from the body. Scientologists endure four consecutive weeks of treatment to achieve this goal.

Two floors below at The Hubbard Guidance Center, participants are “audited”—a loose term for therapy

and evaluation—for sources to their problems. They listen to Hubbard’s audio lectures, stored in rounded plastic folders arranged neatly in bookshelves, and take courses, “Ups and Downs” and “Success through Communication.” In study rooms nearby they visualize problems among groups, using colourful beads, stones, a toy witch hat and a plastic dog figurine Carmichael calls, “demonstration pieces—to help balance ideas with something solid.” The Church often sparks uproar for its radical agenda on psychiatry. Scientologists are notorious for their staunch position against the use of psychiatric drugs to treat the mentally ill. Their belief is that mental illness is not caused by a chemical imbalance in the brain, but by trauma in one’s past life. But you won’t find them consulting texts by Freud or Jung.

Courtesy of the Church of Scientology

In Hubbard’s religion, negative behaviors, ideas and experiences are stored in the “reactive mind”. Slipping into Scientology-lingo, he spoke of treacherous encoded negative experiences, called “engrams”. He aimed to ascend the “bridge” of spiritual awareness, which is accomplished by purging those negative experiences through a process known as “auditing”.

Hubbard introduced counsellor-type “field auditors,” or ministers, who help individuals draw personal life conclusions using a device called the “E-meter.” The electro-psychometer examines one’s stress levels, and indicates patterns of thought which respond to the resistance to the electricity. The participants discuss the trauma until the engrams are released.

It was Hubbard who remarked that “psychiatrist and his front groups operate straight out of the terrorist textbooks,” in his 1969 article “Today’s Terrorism,” published in a Scientology journal. Meanwhile, Tom Cruise was famously quoted on the NBC Today Show saying that “there is no such thing as a chemical imbalance.” Citing Citizens Commission on Human Rights (CCHR), a psychiatry watchdog group, Carmichael says that: “No medical proof exists for the existence of psychiatric ‘diseases’.” And since mental illness is “a moral or spiritual issue,” he says, application lectures and auditing is the solution. Carmichael affirms that “The Church has a strict policy that persons with known medical illnesses for which there are proven treatments — like a broken bone, or the flu, or pneumonia — are sent to a qualified medical doctor for treatment.”

Controversy has long surrounded the Church. Kim Masters reported for Esquire Magazine that “Hubbard’s wife was among a group that went to prison for breaking into and bugging federal offices.” Several articles published by Time in 1991 described the church as a “cult of greed and power,” and “hugely profitable global racket that survives by intimidating members and critics in a Mafia-like manner.” The article also mentioned the Church lost on summary judgment after suing for libel, though they are still petitioning for Supreme Court review.

In response to the allegations, Carmichael asks individuals to visit, read, and ask questions to draw their own conclusions. “You can take a couple of courses like Patrick Swayze or become a Scientologist like Tom Cruise.”

Recently, the reverend identifies a trend of young Scientologists under 35 joining the Church. “Most of them are confident and assertive,” he affirms, suggesting that Scientologists are not only exclusive to troubled members of society. Another misconception he argues against is the Church’s cult-like, secret society appeal. “We are open longer than most churches and we don’t preach anything to you,” says Carmichael, reflecting on an experience where an individual questioned whether Scientologists believe in sex before marriage. His response: “We don’t tell people what to do.”

The Church has undoubtedly earned its reputation for its “eccentricities”, and will always receive its share of criticism for their practices and beliefs. There is also no denying the positive impact they have made in people’s lives. But it’s hard not to be sceptical when reading the quotes of its founder who said, “You don’t get rich writing science fiction. If you want to get rich, you start a religion.”

With an additional three planned expansion projects in NYC, and many others across the world’s attractive city centers, don’t be surprised to see a mission in Downtown Beirut soon.

Additional reporting by Eric Joseph Reitmeyer.

The full featured article in RagMag August 2011 (PDF)

[issuu width=550 height=359 pageNumber=20 backgroundColor=%23222222 documentId=110902194512-3f348039d52b4d1c8df22fbf22d31761 name=ragmag_august_2011 username=ragmag tag=anti%20gravity unit=px id=32080e9b-6fff-81a0-f92b-19d7eca5b4b9 v=2]